Our somatosensory system consists of sensors in the skin and sensors in our muscles, tendons, and joints. The receptors in the skin, the so called cutaneous receptors, tell us about temperature (thermoreceptors), pressure and surface texture (mechano receptors), and pain (nociceptors). The receptors in muscles and joints provide information about muscle length, muscle tension, and joint angles.

Sensory information from Meissner corpuscles and rapidly adapting afferents leads to adjustment of grip force when objects are lifted. These afferents respond with a brief burst of action potentials when objects move a small distance during the early stages of lifting. In response to rapidly adapting afferent activity, muscle force increases reflexively until the gripped object no longer moves. Such a rapid response to a tactile stimulus is a clear indication of the role played by somatosensory neurons in motor activity.

The slowly adapting Merkel’s receptors are responsible for form and texture perception. As would be expected for receptors mediating form perception, Merkel’s receptors are present at high density in the digits and around the mouth (50/mm² of skin surface), at lower density in other glabrous surfaces, and at very low density in hairy skin. This innervations density shrinks progressively with the passage of time so that by the age of 50, the density in human digits is reduced to 10/mm². Unlike rapidly adapting axons, slowly adapting fibers respond not only to the initial indentation of skin, but also to sustained indentation up to several seconds in duration.

Activation of the rapidly adapting Pacinian corpuscles gives a feeling of vibration, while the slowly adapting Ruffini corpuscles respond to the lataral movement or stretching of skin.

Nociceptors have free nerve endings. Functionally, skin nociceptors are either high-threshold mechanoreceptors or polymodal receptors. Polymodal receptors respond not only to intense mechanical stimuli, but also to heat and to noxious chemicals. These receptors respond to minute punctures of the epithelium, with a response magnitude that depends on the degree of tissue deformation. They also respond to temperatures in the range of 40–60°C, and change their response rates as a linear function of warming (in contrast with the saturating responses displayed by non-noxious thermoreceptors at high temperatures).

Pain signals can be separated into individual components, corresponding to different types of nerve fibers used for transmitting these signals. The rapidly transmitted signal, which often has high spatial resolution, is called first pain or cutaneous pricking pain. It is well localized and easily tolerated. The much slower, highly affective component is called second pain or burning pain; it is poorly localized and poorly tolerated. The third or deep pain, arising from viscera, musculature and joints, is also poorly localized, can be chronic and is often associated with referred pain.

| Rapidly adapting | Slowly adapting | |

|---|---|---|

| Surface receptor / small receptive field | Hair receptor, Meissner’s corpuscle: Detect an insect or a very fine vibration. Used for recognizing texture. | Merkel’s receptor: Used for spatial details, e.g. a round surface edge or “an X” in brail. |

| Deep receptor / large receptive field | Pacinian corpuscle: “A diffuse vibration” e.g. tapping with a pencil. | Ruffini’s corpuscle: “A skin stretch”. Used for joint position in fingers. |

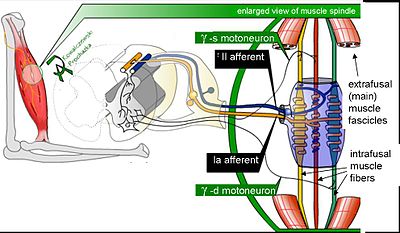

Scattered throughout virtually every striated muscle in the body are long, thin, stretch receptors called muscle spindles. They are quite simple in principle, consisting of a few small muscle fibers with a capsule surrounding the middle third of the fibers. These fibers are called intrafusal fibers, in contrast to the ordinary extrafusal fibers. The ends of the intrafusal fibers are attached to extrafusal fibers, so whenever the muscle is stretched, the intrafusal fibers are also stretched. The central region of each intrafusal fiber has few myofilaments and is non-contractile, but it does have one or more sensory endings applied to it. When the muscle is stretched, the central part of the intrafusal fiber is stretched and each sensory ending fires impulses.

Muscle spindles also receive a motor innervation. The large motor neurons that supply extrafusal muscle fibers are called alpha motor neurons, while the smaller ones supplying the contractile portions of intrafusal fibers are called gamma neurons. Gamma motor neurons can regulate the sensitivity of the muscle spindle so that this sensitivity can be maintained at any given muscle length.

The joint receptors are low-threshold mechanoreceptors and have been divided into four groups. They signal different characteristics of joint function (position, movements, direction and speed of movements). The free receptors or type 4 joint receptors are nociceptors.